The Sadgwars, the Bahá’í Faith and Wilmington, NC

The Sadgwar family has a long-renowned history in Wilmington, NC. They became associated with the Bahá'í Faith early in the 20th century. The family history begins before the abolition of slavery and becomes involved with the religion as early as 1918 when two members of the family, Frederick and Felice, father and youngest of twelve children, identified as Bahá'ís in this early period. Frederick was already long a local, regional, and statewide recognized community and business leader, and later in his life met Louis Gregory. Felice, though young, was already a school teacher among a kin of many college graduates and would work in the schools of Wilmington and other capacities for another 40 years. After the racial strife of the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898 and the scattering of some of the family, some of the kin returned in later decades, including sister Mabel who also joined the religion in her senior years. The general Bahá'í community joined with the Sadgwars in the early 1970s when the total Bahá'í community of the state was near 100. In the 1980s, the sisters were often celebrated both in Wilmington and Bahá'í circumstances, being asked to speak at events. Mabel died in 1986 and Felice in 1988. They gave the home they had lived in and their father Frederick had built as a Center for the Bahá'ís. However, the small Bahá'í community could not afford to keep it but saw to it that the building was protected as a historic site. The Sadgwar family continues to be recalled from time to time in Wilmington's culture and history.

Early years of the Sadgwars[edit]

Heritage and marriage[edit]

The Sadgwar family history begins in Wilmington with the birth of David Elias Sadgwar around 1811[1][2]-1817[3][4][2]-1819.[5][6] The population of Wilmington was about 2000.[7] There were concerns from a decade before, around the time of the independence of Haiti and the French "disgorging" rebellious slaves along the South East including North Carolina as part of the slave trade.[8] Concerns were also ripe from the War of 1812 which ran to 1815 even along the NC coast.[9] The special circumstances of slave life on the coast has also been documented - the singing of Sally Brown sea shanty, the assisting in smuggling slaves among ships with captains sympathetic to their plight, or fleeing and living in the swamps.[10] David's future wife was also born in the period - It is recorded Fannie was born 1817,[5] and blue eyed.[11]

It is family tradition that David was the child of a French sea captain named "Sadgwar”[2] or ("Sadgeward”)[5][12] though this seems an anglicized name. His father apparently was ashore in Wilmington for one night and David's birth mother is unknown. It was reported his mother was white as well but, only because of the illegitimate liaison with a daughter of a prominent white family[11], David was given to slaves, to raise as a slave, despite being "white" from both parents.[13] David was given to slaves named Elias & Sophie who raised him as their own. The biological facts of descent and skin color and being raised in a slave family would play into both the division and unity among races and circumstances as time went on. In the period of David's youth slaves wore badges certifying their owner and legal presence and guards patrolled the area with curfews.[10] The city hosted statewide leading families like Colonial Governors Yeamans and Tryon, and Governors of the State Dudley, Vance, and Russell.[11][14][15][16] Indeed Alex Manly, later noted during the Wilmington Insurrection, was related to governor Charles Manly who's brother lived in Wilmington.[17][18]

It is family tradition that David and his wife Fannie fled to the North after their second child was born and before the Civil War.[13] They made it to New York before being discovered and during the resulting imprisonment their first two children died - according to family tradition they had been fair skinned, had straight hair, and blue eyes.[11] Indeed a few years later Thomas H. Jones, a slave from Wilmington who earned freedom, did flee to the North and wrote and toured giving talks on the evils of slavery.[19][20] After the death of their two babies, David and Fannie had seven further children registered in birth records across 12 years:

Frederick Cutlar (1843-1925), Sophie (1846-1898), Daniel A. (1848–1898), Fannie "Nan" (1850-1917), David Elias Jr.(1852-?), James(1854-?), and George(1855-?). The family also recalls that a kin of Caroline Huggins, David's future daughter-in-law and Frederick's wife, had escaped slavery, served at sea, joined the Navy, returned and bought the slave owner's home after the Civil War.[21][2]

In the Civil War Wilmington was also a place of blockade running and the infectious yellow fever that killed many. Nevertheless freed blacks piloted Union ships into waterways they were familiar with.[10] Union units of armies mustered out of North Carolina did battles in the eastern region of NC,[22] and United States Colored Troops did as well with one company that did come to Wilmington.[23][24] Some 225 units of various sizes were organized on the Confederate side out of North Carolina,[25] with at least four units out of the Wilmington country region.[26] It may also be noted Thornton Chase, generally called the first Bahá'í of the West, mustered out of Massachusetts and served as a white officer leading a different United States Colored Troops company than came to Fort Fisher and was wounded in a battle in Charleston, SC. There were other later Bahá'ís that served in the Civil War as well - Nathan Ward Fitzgerald, Oscar S. Hinckley,[27] John Harrison Mills, and Arthur Pillsbury Dodge served as a drummer boy under his father.[28] The Battle of Wilmington was fought February 11–22, 1865, mostly outside the city after the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in January, and for a time Wilmington became a base of operations for the North.[29]

It is recorded David officially married Fannie Merrick August 11, 1866 in Wilmington[5] but this was a slave/legal matter, and was required by a law passed after the Civil War.[2] Their partnership already included the birth of all their children. Their 24 year old eldest son Frederick had already been at college since the year before and was near graduating, and would be married the next year. The population of the city was near 10,000.[7] David was among the trustees of the reorganized Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church in October, and was noted as a carpenter.[30][2]

After the Civil War it is noted that David was "provided" a plantation out along Castle Hayne Rd.,[11] and soon owned much of the land near the original slave market as well as an early black newspaper.[13] David was also listed as part owner of the newly formed Pine Forest Cemetery in 1868-9,[31] and was listed in the 1870 & 1880 census as a "mulatto" which by definition meant that one parent was white and the other black[5] but this could have been an assumption of the census worker or the context of the times. A photograph of David, a tintype or a Daguerreotype, exists and reproduced in two books: Wilmington: A Pictorial History, by Anne Russell,[11] and Strength through struggle: the chronological and historical record of the African-American community in Wilmington, North Carolina 1865-1950 by William Reaves[2] each who produced a number of local histories.[32][33][34]

Frederick Cutlar Sadgwar, their first surviving son, is the eldest connection of the family to the Bahá'í Faith though it would come late in his life.[35] Frederick attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania,[3] leaving Wilmington sent by his father as soon as it was feesable in 1865 and graduated in 1866.[36] Among the members of his class was fellow Wilmingtonian and later state senator for Halifax county, William P. Mabson.[37][36] Frederick married Caroline Huggins August 8, 1867, daughter of James Bender and Julia Huggins.[35] Caroline was born December 1847 in Wilmington. According to family history she took the last name from her slave owning family.[21] Family tradition also maintains James Bender was a Cherokee Indian.[38]

Frederick and Caroline had 12 children across 25 years:[21][38][35][2] Charles Ward (c. 1868-1952), David C[2](or Elias)[35] III (1869-1908), Caroline Sampson (1871-1966), Frederick C (Jr) (1873-1962), Edward Roane (1874-1973), Norwood (1876 - 1898), Julia Adelaide (1879-~>1900), Byron Taylor (1880-1946), Ernest Linwood (1882-1966), Otis Aubrey (1885-1962), (Frances) Fannie Mabel (usually just Mabel) (1888 - 1986), Felice LeRoy (1893-1988).

Enterprises[edit]

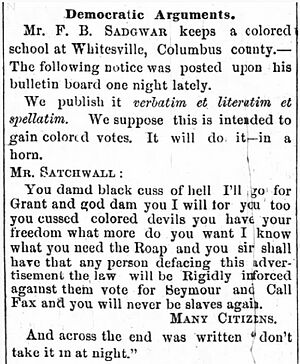

A year after being wed, a few years after the Civil War and attending university for two years, and the same year as their first child, Frederick was threatened in Whiteville, Columbus County, for running a school for former slaves[39] in the next major town some 50 miles west of Wilmington.

As an aside you can already see politics are entering into it too, aside from the threats and violence of which more is to come. But people will try politics along the way too, and that unfairly.

In addition to this school to the west, family records include a signed letter from the superintendent of the Wilmington schools asking Frederick to be a teacher,[21] by founding that school in Whiteville.[11] In January 1869 Frederick read Lincoln's Proclamation of Emancipation at the third observance in town.[2] In October Frederick was listed among "teachers and missionaries" for the American Missionary Association(AMA),[40] and the next year Frederick was one of the secretaries of the town committee celebrating the 15th amendment to the Constitution[41] prohibiting the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude". It was ratified on February 3, 1870.[42] The parade went on despite torrents of rain. In the Fall Frederick helped found a tradesmen union - the “Mechanics Association” bringing together a number of stone masons, carpenters and painters - and he had a position in the association as “W. Computer”.[43][44] You may recall from the movie Hidden Figures in this era people who were called “computers” were mathematically skilled and checked people’s work. So Frederick was literate and knew math to the point of teaching and checking other people’s work, active in the community and beyond. A text refers to Frederick and Caroline as slaves at the time of Caroline Sampson (Carrie)'s birth,[45] but perhaps it is confused of the timing or interpreting the circumstances or was even a mix up and her report was actually about her grandfather learning letters - it refers to a friend teaching letters on a slate then destroyed with a jack-plane while her mother was not literate at the time but learned later. Other slaves letters were recently discovered in hidden joints of plaster in Wilmington.[46]

Wilmington had gained a signifcant black police force and black militia in the latter 1860s into the 1870s.[10] Black state senator Abraham Galloway represented the area and some 6,000 people attended his funeral in 1870.[10] Business and trade was thriving and 59% of the population of the city and nearly that of the county was black that year.[47] Sadgwar family history held that the city was not segregated during the time.[21]

It is clear the entire family was furthering the success of David Elias Sadgwar and supported education. Frederick’s younger brother Daniel was also a graduate of Lincoln 1867,[48] went on to finish Howard University in 1871,[49] was finishing at Harvard the next year,[50] and took a position clerking for the federal government.[51] Sister Fannie was a teacher at the Williston School run by the AMA in Wilmington.[52] The school itself dated to just after the Civil War but had the reputation that there were no black teachers before 1874.[53] The school would add grades up to the high school grades as time went on. More instances of education would appear among David's grandchildren. This was the year Frederick's mother died, August 3, 1872.[5]

One of the Sadgwar family homes was noted burned in a fire on the roof in 1873,[54] and in 1875 Frederick was petitioning for funding a fire truck for one of the firemen brigades as its secretary.[55] That year Frederick’s sister Fannie “Nan” was part of the first “colored” state fair which was held in Wilmington by having a dress on exhibition.[56] Frederick showed a well developed collection of native woods.[2] In 1877 state governor Vance had called for a coordinated effort among colored populations of the state to establish a State Normal School to train "colored" teachers.[57] Frederick was asked to be secretary of the Wilmington organization. By about 1878 brother Daniel was back in town living with David at one address and Frederick was living at another.[58]

In 1880, by now father of seven children, accomplished business and education community leader, Frederick was a Republican delegate of the third ward,[59] (in the post-Civil War Era thanks to Lincoln almost all blacks joined the Republican party,) and was a secretary in a black insurance association.[60] In May 1881 the Marine Hospital[61] was renovated[62] and Frederick was listed as one of the laborers being paid.[63] In inflation adjusted terms he would have been paid well over $2000 for his work. In 1881 Frederick was also an "immaculate" of the local AME church.[64] That year David was in charge of constructing a guano processing structure that was shipped to Baltimore.[2] In 1883 Frederick was getting involved in the debate of a railroad extension to Wilmington aiding in estimating the cost per mile of the work.[65] The next day Frederick reported that though the committee hadn’t finished the work they did get an estimate from another company and, all matters being settled, joined the committee to see to the establishment of the railroad extension.[66] Frederick remained among the stockholders and Daniel joined the board of directors.[2] Fifteen years after starting as a community leader and businessman, a few months later Frederick was on a list of jurors for the court,[67] (thus also a property owner,) and about the same time Frederick served as one of the first wave of mail carriers, at the age of 40 yrs old, and worked the job for two years.[68]

Starting the wave of David's grandchildren going to college we have Frederick's eldest son Charles at Biddle University in Charlotte[69] circa 1883-4.[70] Carrie attended the Wilmington Gregory Institute in her youth and was commended to Fisk.[45] More on that soon.

A Mrs. Sadgwar - unclear exactly who, perhaps Frederick’s wife, went to Washington, NC, to “visit relatives and friends” in 1883.[71] Washington, NC, would later be a locus of Bahá'í activity.[72]

In 1884 Frederick was a poll worker for Wilmington's third ward,[73] and was on stage as one of the town leaders hearing a talk about West Africa,[74] around the time of the peak of the emigration to Liberia. A house built by David burned down in 1885 and was immediately rebuilt.[2]

In 1887 the Knobloch family, later Bahá'ís and influence on many early Bahá'ís related to NC, appeared in Wilmington, alas with the passing of Pauline’s father.[75] That year Frederick was nominated for the Republican primary.[76] Brother Daniel was employed for the US Senate for some of 1884, being paid (not inflation adjusted dollars since then) $2.50 a day or $77.50 for a full month,[77] and then being paid at $80/mth for some of each Spring/Summer/Fall of 1887, and then the month of April 1888.[78]

The Insurrection and the Sadgwars[edit]

Keeping in mind ahead of us we have the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898 where whites rioted against the black community, we have the beginnings of visible political strife in a conflict over a letter to the newspaper by a Judge Russell who called black people savages incapable of governing. “Independent Republicans” styled themselves “Judge Russell’s Savages” held their own convention and Frederick’s youngest brother George was a member of the committee to nominate county officers. Frederick was nominated for coroner.[79] Frederick’s younger brother James was nominated for state senator of the region.[80] Frederick refused to run to be coroner,[81] Circa 1888-1889 Daniel was noted living in DC and co-inventing a folding chair.[82] That year Daniel was also noted employed during 1888-9 for the Senate possibly for the entirety of a year's period in there (the annualized salary working out to $80/mth for a 12 mth term.)[83] Their father David Elias Sadgwar died May 23, 1889, and was buried in Pine Forest Cemetery.[2]

The Knobloch's were last known in Wilmington in 1889,[84] and were definitely known in DC in 1893.[85] In 1889 the town’s black doctor died and Frederick, now the father of 11 of his 12 children, was among his pall bearers.[86] Also in 1889 Caroline Sadgwar, Frederick’s wife, was listed as an owner of some land in town.[87] And again Frederick was listed as a poll worker,[88] and four people even voted for him.[89]

In 1890 Frederick was again a juror for the local court.[90] Two children of Frederick - Carrie and David Jr - were listed finishing at the local "Gregory Institute" school then too.[91] Frederick was again a poll worked in 1891.[92] Carrie Sadgwar, Frederick’s eldest daughter, was noted attending Fisk University the same year.[93] This was also later well known Bahá'í Louis Gregory’s first year at Fisk,[94] and commented they did meet.[95] They were both at Fisk for four years; she was a year ahead of him. Gregory was listed as a Freshman from Charleston for 1891-2, graduating 1896,[96] and teaching at a school in Nashville in 1897 - the particular bound collection of the Fisk Catalogue is missing the 1890-1 edition so Caroline was not listed as a incoming Freshman but was listed as a Junior in 1891-2, and graduating 1894.[97][98] About a decade later Gregory would attend multiple talks with Pauline Knobloch Hannen in DC and join the Bahá'í Faith.[94]

That year Frederick also served as secretary of a meeting honoring a priest of a local church,[99] and the Frederick's household held a reception for saying farewell to a minister in August.[100] Daughter Julia, one of Frederick’s younger daughters, at 13 yrs old, was listed was an assistant at the Bricks school near Enfield in 1892.[101] Bricks founding leader was Thomas Inborden, another Fisk graduate.[102]

Frederick was again a delegate for the third ward in 1891,[103] and in 1892 it was noted in particular that Frederick was among the speakers at a corner on the streets.[104] That Fall ballots for Sadgwar and others were thrown out because they weren't on white paper.[105] Still he was listed in elections in 1893,[106] while continuing to be a poll worker.[107] Another cycle of being a juror came again in 1893 as well.[108] This was also when Frederick’s youngest child was born - Felice, destined to be among the first Bahá'ís of NC,(see below.) Also circa 1893-5 son David Elias the III was at Howard University,[109] and son Fred finished Biddle University in 1893.[110][70]

In 1894 the Knights of Pythias formed a chapter in Wilmington and Frederick was published as a member.[111] The Knights are a fraternal organization founded in 1864 with values of loyalty, honor, and friendship and requires belief in a supreme being.[112] That summer Frederick also joined a broad businessmen’s alliance to set up an association as its secretary.[113] A statewide conference of the Knights of Pythias met in Wilmington and Federick picked up a statewide position in the organization.[114] The new year of 1895 opened with a celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation at which Frederick's daughter Carrie was present.[115] A few days later Frederick was elected to the board of a new local “United Charities” association.[116] Still in January, Carrie sang at a fund raiser for one of the humanitarian organizations.[117]

Another harbinger of the tensions rising towards the Insurrection came later in 1895 when an interracial meeting[2] of Republicans Frederick was in was overrun by a mob against the organizing of black people.[118] This division then manifested in the meetings of each side,[119] and there was a letter published in the mid-west of the state a year later noting that the election of the white leader was highly controversial and Frederick was among the black leadership in Wilmington not supporting the white leader[120] as was Daniel.[2] The next state wide meeting of the Knights of Pythias again had Frederick as an officer of the association but was advertised out of DC instead of locally.[121] The next year Frederick then paid an official visit to the Knights in Charlotte, and this was published in Raleigh,[122] and another year serving at the state level followed that summer.[123][124] And back in Wilmington Frederick was among the partners in a new Livery Stable horse business that summer too.[125] So despite rising tensions Frederick's own work had clearly entered a state-wide awareness.

In January 1898, the year of the Insurrection, came the news of the death of Frederick’s younger brother Daniel, who had been a Howard and Harvard graduate and carpenter for the US Senate, who died suddenly while working at a flour mill in Wilmington between 7 and 7:30 in the morning.[126] One of Frederick’s sisters died a month later (Sophie; it comes out later that the other sister Fannie was the executrix of her will[127] and taxes were owed on some land in 1901.[128])[129] Another kin died in March - this time son Norwood.[130] Two police related incidents are then reported. A kin of Frederick, possibly one of his sons, was cut in a fight and the assailant arrested.[131] Another Sadgwar had his bicycle confiscated for lacking a bell ringer, contrary to the ordinances of the city, and this Sadgwar was actually taken down to the courthouse to appear before a judge for the offense.[132] That was in June.

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898 began in November with a hostile white “committee” summoning black leaders on the matter of Alexander Manly’s newspaper editorial[133] - Frederick was among those summoned.[134] Frederick was among the black leaders recognized in the period.[135][135] An interview of Lewin Manly, grandson of Alexander Manly, mentions the Sadgwar family had not being banished.[136] Lewin learned separately that during the insurrection Mabel and Felice had been in the school and an older brother (alas all the brothers were older and around so don't know which,) was to get them “during the mayhem”. Daughter Julia was listed as at Fisk, graduating in 1899.[137] News of the riot reached London the next day.[138] Carrie was singing in London as part of the Fisk Jubilee Singers from around November 1897 to October 1899;[139][140] "I stood on stage that night to sing my solo and my voice quivered and stopped."[141] Son Byron was serving in the US army/navy,[142] then living in New Jersey.[143] He served on the USS Vermont, Wasp (blockade of Cuba), as part of the Spanish-American War, and then the USS Franklin.[144]

"Newly appointed mayor Alfred Moore Waddell offered Collier’s Weekly a first-hand account of the Wilmington Race Riot. His account provided the structure and substance of the collective memory of events for nearly a century. Waddell’s story whitewashed the bloodshed and disorder that historians have since associated with the riot.”[145] Various chapters of the 2006 state report on the Insurrection mentions the Sadgwars.[146][147][148][149]

In 1899 Frederick bid on repairing a bridge damaged by storm flood and lost even though he underbid - all reported in the newspaper.[150]

Post Insurrection and the Sadgwars[edit]

Mabel was 10 years old when the Insurrection happened - she recalled growing up bitter and feeling "I was a Negro" though teachers remained on friendly terms.[21] For the first time since, 1882 there is no mention yet identified of the Sadgwars in the local newspapers in 1900. Indeed, from now on, there has been a clear decrease in Frederick's visibility in the local papers, and despite not being banished by the mob, several Sadgwars were soon away. Frederick was now some 55 years old and had been a local, regionally active, and statewide recognized leader before the Wilmington Insurrection. Now his family included those driven out by it. Carrie Sadgwar, who was very dark skinned, married Alexander Manly, victim at the center of the Insurrection, who often passed as white,[2] in Congressman George Henry White’s[136][151] home with the news mentioned in a couple diverse places like Baltimore, Maryland,[152] St. Paul, Minnesota,[153] along with DC.[154] The wedding was announced just a few days before.[155] The betrothal was actually before the Insurrection and Frederick had built a house for them.[2] The year prior to the wedding Carrie was listed as principal of a school in Wilmington through the Fisk Catalogue of alumni.[156] About a week before the wedding Carrie was in Wilmington for a Memorial Day parade she sang at.[157] Louis Gregory was in DC by then,[158] but he was not yet working for the government - he began to work for the Treasury Department in 1906 where he heard of the Bahá'í Faith and was not yet even a practicing lawyer until 1902.[94] Fredericks’ namesake son injured his eye later that year too.[159] Daughter Julia Sadgwar worked at the Enfield Brick's school again that year[160][137] and would on through 1909.[101] Frederick's brother George was next known in DC in 1911 as a public school teacher.[161]

But as was said, the Sadgwars generally stayed in Wilmington. In 1902 Frederick’s daughter Mabel performed a piano piece as part of graduation year at the town Gregory Normal Institute.[162] That Fall Julia, now close to 24 yrs old, went off to visit friends in Washington, NC - indeed among the visitors were people from Pennsylvania and Illinois as well and the newspaper story mentioning the event itself was published in DC.[163]

Around 1903 a business of Frederick's - the "Afro-American Mercantile Company" was registered with the State.[164] The Knobloch-Hannen family, partly from Wilmington but moved to DC, was closely encountering the Bahá'í Faith.[165] In Winter of 1901-2 Mírzá Abu'l-Fadl, there through 1904, and Laura Barney were among the active Bahá'ís of DC. In another few years several African-Americans from or related to NC would hear of the religion either from Pauline Knobloch Hannen or through somebody associated with she and her husband - most notably Louis Gregory though that remains a few years in the future. Before him there was Caroline York and Pocahontas Pope. But it would be Gregory that would make the most trips to NC over the coming many decades.

In 1904 a fire at the Bricks school for African Americans at Enfield, NC, burned down and Frederick undertook gathering materials for students.[166][167] At the end of that summer it comes out that Fannie, Frederick’s sister, not the namesake daughter, was the executrix of their sister Sophia’s Will and other beneficiaries of the Will were not available for settlement so it had to be settled in court.[127] The land was sold in 1905 at order of the court.[168] A couple months later Frederick was among the trustees of the Chesnut St colored Presbyterian church which was seeking to build a parsonage.[169] Meanwhile son Charles married in New Jersey in 1904.[170]

Catching up on the Knoblochs, Pocahontas Pope joined the Bahá'í Faith around now. She grew up in Halifax county near Bricks, and then had connections with the black school at Rich Square, NC, where her husband had been principal, and Raleigh where he grew up, but at this time she worked for/with one of the Knobloch sisters.[171][172]

In 1907 Alexander Manly and his wife Carrie Sadgwar Manly sold some land in town to Frederick, (this may have been the home he had built for them.)[173]

This period circa 1906-1910 would later have connections with the Bahá'í Faith and North Carolina. We don’t know much of the details but during this period Louis Gregory had[174] quickly become a rising community leader in the black community of DC including being a counter sitting protestor at the Capital, writing letters to the editor deploying the lynchings going on across the South, and being elected to the DC Bethel Literary and Historical Society leadership and eventually president, and then encountering the Bahá'í Faith, joining the religion in connection with the Knobloch-Hannens, going on pilgrimage, and on the return trip through Germany stoping to see a Knobloch sister. All these connections to Wilmington perhaps lead to a trip to Wilmington in less than a decade, and other trips before that to other places in NC that we know of. In particular Gregory’s known first trip to NC was in 1910 but so far as we know he only stopped in Durham.[94] Felice Sadgwar was noted outside of Wilmington in 1910 working as an assistant at Lincoln Academy, King's Mounting, NC, west of Charlotte, at about the age of 17[175] working for the same institution that ran the black school at Bricks and that her father had worked with since after the Civil War. Also there is the connection between Carrie Sadgwar Manly and Gregory to be mindful of - though the Manly’s had moved to Philadelphia[176] they could have kept in contact with developments and Gregory’s rising status in DC and may have heard of Gregory's religious involvement.

In 1911 Hubert Parris was noted approaching the vicinity of Wilmington.[177] Hubert had encountered the Faith while as a Christian minister presenting at Greenacre some years earlier. Soon he would move to Wilmington and more would change in his life. In 1912 Felice was back graduating in Wilmington at the Gregory Normal Institute;[178] she was the valedictorian among the six graduating students.[179] Felice recalled her valedictorian speech calling for raising people to be citizens of the world and not just North Carolina.[21] However Felice also recalled being denied the graduation diploma because she wore, according to the administration, a silk dress.[21] That year two daughters were teachers in Wilmington schools: Julia and Mabel.[180] In 1913 two or three of the Frederic's daughters were involved in a local (segregated) flower decorating contest.[181] And Mabel was again listed as a teacher from 1913 for some years at the Williston school.[182] Felice also worked at a number of NC schools across 1913-1915 through the AMA.[183][184][185][186]

In the Fall of 1915 Hubert Parris had settled in Wilmington, come as a certified doctor and minister. He began to hold free clinics in the schools, speaking at schools and rallied black farmers to contribute and organize food relief during the period of World War I.

Connecting with the Bahá'ís[edit]

In 1916 there was a newspaper piece mentioning that Frederick’s home was broken into but nothing stolen - along with two other homes that night.[187] Mabel also attended the summer school at Greensboro A&T College in 1916.[188] She continued working for the Williston school, joined by Felice, in 1917.[189] Another land dispute had to be settled with Sadgwar kin, (noting son Fred was now married,) vs an absent family relation in 1916.[190] During this time Frederick's sister Fannie died.[191] In 1917 Felice and, perhaps a grandchild of the family or other kin, Annie, won prizes in the black regional fair in "fancy work” (sewing?).[192] In 1917 Felice and Mabel served as assistants in court.[193]

Since we don't know how the connections with the Bahá'ís came to be we'll explore some things in the vicinity. Gregory was at Fisk in December 1916,[96] and by March was in Wilmington, Delaware,[194] before ending up in Maine in August.[195] We don't know if his trip to Fisk or back connected with any Sadgwars. Joseph Hannen and Pauline Knobloch Hannen visited Wilmington August 1917.[196] We don’t know if they met with the Sadgwars. Another point is that Felice was in New York in September 1917, just before school started in the fall and ahead of the 1918 pandemic.[197][198] Roy Williams own Bahá'í life begins in Brooklyn in 1918. And Felice was not the first Sadgwar in the city. Charles, a brother of Frederick, had a letter waiting for him Brooklyn in 1887.[199]

In 1918 Hubert Parris gave a talk for the observance of Emancipation Day in Wilmington.[200] Mabel and Felice were noted teaching still and through into the 1920s[201] Brother Ernest' draft registration card noted in September 1918 that he was partially paralyzed.[202] Brother Otis' noted he was in good health and was working as a clerk for the railroad Atlantic Coast Line company.[203]

Gregory made a trip to NC, including Wilmington in spring 1919, certainly by early April.[204][205] This included writing a letter back to Joseph Hannen that he was pressing on to South Carolina before the national convention,[204] (the one the Tablets of the Divine Plan were to be unveiled.) Most significantly, in this letter Gregory credits the first connection to Roy Williams, though how and when are not stated. Gregory’s trips are known to have contacted the Sadgwar family at least in the 1920s.[206] Felice was specifically named in a Bahá'í publication by Williams in 1923.[207] In 1925 later Gregory speaks of a Bahá'í community in Wilmington, where he had spent the month of January.[208] This “young woman”, he says seven years before 1925, meaning around 1918-1919,[208] seems most likely to be Felice Sadgwar. Mabel, the only other sister in town, was known to have joined the religion decades later, (see below.) Carrie is known to be living in Pennsylvania in 1919 helping establish a "Fisk Club" with Carrie as its first president (even noting her address then was in Lamot, PA.)[209] Carrie was also never mentioned as joining the religion.

Bahá'ís also had contact with folks in Washington, NC[72] - specifically Dr. W. H. Carter's wife, Lula Rawls Carter,[210] was sister to early Bahá'í Hooper Harris' wife, Sarah Gertrude Rawls Harris.[211] The Carter family had moved in circa 1908.[212] The Carter family also knew the Beckwiths.[213] Kate Beckwith was Principal of East Carolina Teacher's Training College from 1909 to 1925 in Greenville,[214] to whom these Bahá'ís were commended as they headed west.[72] Beckwith had previously opened a school in Washington, NC,[215] and Lula had been working on renovating or making a new school for the black population of Washington.[72] We don't know if Felice or Frederick were present in town for their presentations including this discussion of a new school.

Post War[edit]

Unfortunately the Wilmington Morning Star, a key newspaper covering these events, falls silent in 1922 in the searchable archive. Mabel later said she married Thomas Manly, brother of Alex Manly,[2] and moved to Philadelphia, but a date closer to early 1920s is supported - but that in Philadelphia she felt no prejudice and picked up gardening.[21]

By 1922 there was evidence Parris was less active as a minister and he was not listed as a minister after 1924. He also moved out of Wilmington at some point and by 1930 is noted living in Rich Square, NC, where Pocahontas Pope and her husband had worked in a school several decades before and after which she had joined the Bahá'í Faith.

Felice was named as a Bahá'í in a Bahá'í publication about education in 1923.[207]

In January 1925 Gregory spent an extended time in Wilmington:

Wilmington NC during January (1925) afforded many opportunities for service. In this city there lives a truly remarkable believer. A young woman who for seven years has been devoted to the Cause under most difficult circumstances. At present her long trials and sacrifices are bearing fruit and Louis Gregory feels that in this city an Assembly will soon be organized. In Wilmington meetings were held daily in churches, with the Ministers Union, in the public schools, and in many private homes. An influential Catholic invited Louis to address a gathering of Catholic young people in Wilmington and the response was so enthusiastic that he was invited to return.[208]

Family history claims Gregory stayed with the family and this was when Frederick joined the religion.[216] Felice explained, "My father was always searching for that togetherness that the Christian faith didn't have." when she was 95. His involvement with the religion was acknowledged in the 1998 Strength through struggle: the chronological and historical record of the African-American community in Wilmington, North Carolina 1865-1950 published by the New Hanover County Public Library.[2]

A Bahá'í Race Amity Convention was hoped for in April, 1925, perhaps in DC, but was postponed though Gregory spoke of someone who might help with it.[94] Alas the postponement of the convention became alittle prolonged.[94] Frederick died May 30, 1925, after a prolonged illness,[217] was buried June 2,[218][219] attendees including Alex and Carrie Manly,[220] and came to be known in Bahá'í circles as the first Bahá'í of NC in later years[30][95][221][35] though his name was unrecorded at the time.

Gregory made a trip to the South from October, 1925, but was in Florida and Georgia mostly.[94] Alain Locke, a Bahá’í since 1918,[222] also did a speaking tour of the South for the religion starting in 1925 but what states is less clear.[94][223] By July, Felice attended Columbia University in New York City with some friends.[224] New York City Bahá'ís had “according to the recent testimony of an impartial and qualified observer… a real fraternity between black and white, and an unprecedented lifting of the 'colour bar', described by the said observer as 'almost miraculous'".[225] See Coverage of the Baha'i Faith in New York City via the New York Age newspaper. But it is unknown if Felice was aware of it. This appears to be a period where Felice did a lot of traveling. Felice and friends went to visit Pittsburgh in August.[226] Felice and the friends are back in Wilmington by later September.[227] Of the winter of 1925-6 Felice ("Miss Sadgwar") is mentioned in a report of the Bahá'í Southern Regional Committee report offered at the spring 1926 annual convention as being "working as ever."[228] In Spring 1926 Felice and these ladies were visible at a Valentines Day reception in Wilmington, DE.[229] That following Summer Felice was among those at a reception party in Wilmington, NC and then off to Philadelphia.[230] In 1927 she played music as part of a wedding in Pittsburgh.[231] Another 6 months later she played piano accompaniment at another performance in Pittsburgh.[232]

Gregory did make a trip through NC in 1928 but so far the trip only mentions Durham.[94]

Felice would have been minding her mother's care in later years. She was also sick in 1929 - son Otis made the trip down from Baltimore to see her.[233] Brother Fred Sadgwar Jr was a funeral director.[234]

Approaching modern times[edit]

In 1930 Felice was a teacher at the Williston school.[235] In the 1970s a Bahá'í News piece mentions Bahá'ís were leading the Bricks school at Enfield in the early 1930s,[236] and Gregory visited it in 1931 and another year.[94] However the AMA canceled plans for an expansion of the school in the face of the Great Depression and instead the school was closed in the Fall of 1933 much to the pain of the local residents who had built up a community around it.[237] Another Bahá'í, Sarah Elizabeth Martin,(later Pereira) began working at Shaw University in Raleigh in 1933 and continued through 1942 - her parents were from Raleigh but they had moved away by the turn of the century and then learned of the Faith from Gregory while living in Cleveland. It is unknown if Sarah and Felice knew of eachother.

In 1932 Felice was on the board of the United Charities her father had helped found.[2] Mother Carolina Huggins Sadgwar died September 12, 1932 in Wilmington.[35] The next visible reference to Felice in the newspapers, minding we are presently blind to of a significant source in Wilmington, was in 1934 when Felice managed to be noticed vacationing to New York and stopping to see her sister Mabel, (Mrs. Thomas Manly.)[238] It was later noted Felice had already been serving in emergency relief planning from Wilmington serving from 1932-5.[239][240]

In town a playground was constructed and donations from Frederick were acknowledge in 1936. That year Sarah,[211] wife of early Bahá'í Hooper Harris, and her sister,[210] who had contact with other Bahá'ís traveling through the state in 1919, died in Washington, NC. It is not known if Felice had had any contact with them. Felice was also listed affiliated with the Fayetteville State Teachers College, as it was known then, with an "Extension Center" in Wilmington in 1937,[241] another Extension Center in Elizabethtown in 1939,[242] and with the college itself in the summer of 1940.[243] Julia Sadgwar died in 1944,[2] and brother Byron died in 1946.[142]Meanwhile and the first spiritual assembly of Bahá'ís in North Carolina was elected in Greensboro in 1943 and Hubert Parris officially joined the religion the same day.[244][245] Felice was also there at the Fayetteville State Teachers College in the summer of 1953.[246] Parris died in 1956.[247] In 1947-8 Felice was a teacher at the Wrightsboro School, which alas burned down that year and the school merged with the Peabody School.[2]

In 1952 Felice's eldest brother Charles died.[248] In 1958 Felice wrote a letter to the editor of the Ebony magazine.[249] Though the religion had been visible in various nationally and statewide circulated black newspapers[250] it should be noted Ebony had several articles in the 1950s and 60s on the religion.[251] It is not known if Felice noticed the coverage. Mabel moved back to Wilmington around 1959.[21]

Otis Sadgwar, living in Wilmington again for some years and part owner of the Sadgwar Funeral Home, died in December 1962.[252][253] That summer Felice retired from teaching.[254] From around then Felice began to volunteer at the Retired Senior Volunteer program.[38] Carrie (Caroline) Sadgwar Manly died in 1966,[255] as did brother Earnest.[256] The “Sadgwar sisters” are noted a few months later in Wilmington holding a “Garden Market” benefit for the Chestnut St. Presbytrian Church in October.[257]

Shortly before Bahá'ís from the wider area moved to Wilmington because of excitement in South Carolina,[258] in 1969 the “Sadgwar-Manly Garden” was among the private gardens opened to an azalea tour in Wilmington.[259]

Where North Carolina might have had no enduring communities of Bahá’ís before 1942, there were about 20 Bahá’ís in 1944,[260] and around 70 in 1963,[261] it may have been approaching over 100 adults in 1968.[262] At a conference of Bahá'ís a summary of the North Carolina community noted there were 30 localities with Bahá'ís, and 6 assemblies.[263] Goal cities listed were - Ahoskie, Asheboro, Boone Clinton, Concord, Cullowhee, Dodson, Eden, Elizabeth City, Gastonia, Goldsboro, Henderson, Hendersonville, Hickory, Jacksonville, Kinston, Laurenburg, Lumberton, Marion, Monroe, Morehead City, Murphy, Roanoke Rapids, Salisbury, Smithfield, Washington, Wilmington, Wilson - and some of these already had at least one new Baha'i since Ridvan 1969 - Gastonia, Morehead City, and Roanoke Rapids.[264]

Reconnecting with the Bahá'ís[edit]

Circa 1971, after Bahá'ís had populated various parts of NC including the Triad and Triangle, Asheville and Charlotte, Bahá'ís came to Wilmington pioneering and discovered the sisters present, still alive, with recognition of Felice and her father, and the new addition of Mabel as members of the religion.

Please help improve this article or section by expanding it. |

In September 1972 Diana DeChesere was noted secretary of the New Hanover County Assembly, surrounding Wilmington.[265] In 1973 Felice and Mabel's brother Edward died.[266]

In 1975 Felice and Mabel were interviewed about the Wilmington Insurrection as research background for books,[267] and 1977.[135]

The integration of the Sadgwars with the Bahá'í community was such that by 1978 the Sadgwar home hosted a publicly advertised Feast.[268] Next it held the observance of the Birth of the Báb with a slideshow by Frank Stewart of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and regular meetings on Sundays.[269]

In 1979 Felice attended a Chestnut Street United Presbyterian Church dedication service of a piano and new stained glass windows.[270]

Felice also went to speak at historic Wilmington events such as the New Hanover County Museum in 1981,[271] and recalling elders who had passed and been buried.[272] Both sisters were profiled the summer of 1981.[21] In fact it noted Mabel had blue eyes and contributed to the New Hanover Library oral history program as well as a thick folder of documented materials. Roger Hamrick wrote a letter to the editor in thanks for the story and referred to Frederick as the first Bahá'í of the city and Mabel joining the religion in her later years after returning from living in Philadelphia.[221] Timed with a comment of the Universal House of Justice about the religion emerging from obscurity,[273] a North Carolina historic marker and tribute for Frederick and his house was set with talks and coverage in 1982 during human relations month,[274] followed by Felice being profiled and pictured having won "Citizen of the year". She was quoted saying "What America needs today is to get rid of its racial and religious and political prejudices."[38]

In 1983 the city sold some land originally deeded to the Sadgwar family.[275]

Felice and Mabel were interviewed by various Bahá'ís but available archives have not been published. In this period their notoriety was high and many Bahá'ís of the region met them.

In 1984 Felice’s sister Caroline (Carrie), and Felice were recognized as Wilmington Women during history week.[276] In 1985 Felice and Mabel attended the Azalea Queen presentation at the New Hanover County Museum.[277] A month later Felice sang at the Shuffler Senior Center.[278] Another couple weeks later Felice and Mabel were interviewed for history research on the Insurrection.[279]

Mabel died near a year later, in early May, 1986.[280] Several months later the Bahá'ís of Wilmington were profiled.[216] Emerging more obscurity, a statewide review of religions was produced with one author out of Wilmington and mentioned the Wilmington community and heritage in 6 pages spread with many large pictures featuring Louis Gregory, the Sadgwars, Bahá'ís elsewhere in the state, many names of Bahá'ís from the 1960s, the formation of some Assemblies, and the persecution of Bahá'ís in Iran.[281] They described the religion as "principally nonwhite". And a picture of Felice with two children on her lap closed the text of the book.

Felice died in July, 1988, though the newspaper account praising her mixed up her father's name with that of Louis Gregory.[282] A commemoration was held the next year.[283] Historical research recalled David Sadgwar in 1989,[284] and Frederick was noted as well.[285]

Remembering Sadgwars[edit]

Please help improve this article or section by expanding it. |

In 1989 the estate of Felice Sadgwar had given $1000 for more than one year to the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.[286]

Sites of district conventions of Bahá'ís were published in August as 1991 - one was hosted in Wilmington:[287] Unit 80, "Eastern-A in Wilmington" was held October 6 at Sadgwar Bahá'í Center arranged by the LSA of Wilmington, and absentee ballots could be sent to Joan Canterbury.

The Spiritual Assembly of Wilmington established the Felice L. Sadgwar award in 1993.[288] The Sadgwar Bahá'í Center hosted a meeting on prophecy in 1994,[289] and classes on the religion in 1995.[290] The Sadgwar House was included in a Heritage Trail, itself a student lead project as part of some course work, in 1997.[291]

There seems to have been a Frederick C. Sadgwar Mathematics Award (recall he was a “computer” in his day) in the high school some years - occasionally as “TC” or “FC”.[292]

1998 was the centeniary of the Insurrection and several events noted the Sadgwars. The New Hanover Library published Strength through struggle: the chronological and historical record of the African-American community in Wilmington, North Carolina 1865-1950 and the writer, William Reaves, acknowledged that Felice and Mabel had "spent many enjoyable times with me, helping me to realize the importance of recording Wilmington's black history".[2] A picture of the christening of the son of Carrie Sadgwar Manly and Alexander was published.[293] The house was part of an historic tour in 1998 as well.[294] A local play of the Carrie-Alex marriage and history was put on the stage as part of the centennial events.[295] A dedication stone remembering Felice was placed at William H. Blount Elementary School the next year.[296] The Bahá'ís held a race unity festival as well.[297]

The Sadgwar home acting as a Bahá'í Center was not sustainable and it was sold in the later 1990s.[citation needed] Regardless, an article on the history of events including the Sadgwars was published in 2000,[298] and in 2002 there was a series of articles.[299] Articles referencing the history also came in 2003[300] and 2004 as well.[301]

In 2012 the memorial stones including of Felice Sadgwar were uncovered at the new Mosley Performance Learning Center, formerly the Blount Elementary School.[302]

In 2014 new inductee of the Wilmington Walk of Fame, Grenoldo Frazier, thanked Felice for teaching him piano.[303]

Further reading[edit]

- William Reaves (September 1998). Tabith Hutaff McEachern (ed.). "Strength through struggle": the chronological and historical record of the African-American community in Wilmington, North Carolina 1865-1950. New Hanover County Public Library. ISBN 978-0-9670410-0-1.

- Anne Russell (2004) [1981]. Wilmington: A Pictorial History. Donning. ISBN 9781578642526. OCLC 55047136.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ William McKee Evans (1 October 2010). Open Wound: The Long View of Race in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-252-09114-8.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 William Reaves (September 1998). Tabith Hutaff McEachern (ed.). "Strength through struggle": the chronological and historical record of the African-American community in Wilmington, North Carolina 1865-1950. New Hanover County Public Library. pp. xiii, 3, 44, 58, 138, 168–244, 294–297, 311–328, 378, 455–459. ISBN 978-0-9670410-0-1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sadgwar Family Home, African American Heritage Foundation of Wilmington, 2009

- ↑ Devoted to the interests of hs race: Black officeholders and the political culture of freedom in Wilmington, North Carolina, 1865-1877, by Thanayi Michelle Jackson, Dissertation in the Department of History, University of Maryland, 2016, pp. 39-40

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Genealogy Report: Descendants of David Elias Sadgwar, by Charles. M. Uzzell, genealogy.com

- ↑ David Elias Sadgwar, Sr, Find-a-grave, by L. Pearson, #146646037, May 18, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Timeline of Wilmington, North Carolina, Wikipedia, May, 2017

- ↑ "In August, 1802, Colonel William Davies of Norfolk, Virginia, wrote to Governor James Monroe that 'a French frigate from Cape Francois full of negroes [was] off Cape Hatteras … and that … it was the determination of the French government to transport from St. Domingo such of the blacks as had borne arms against the French.' Later, a Virginia newspaper protested that "the infernal French are disgorging the whole of their wretched blacks upon our shores." In the subsequent hysteria, all Alexandria townsmen were apparently as anxious to fight the French as the Negroes. According to one eyewitness, the citizens were prepared to kill all the Negroes who landed, a group estimated at one thousand. Congress received a memorial from the citizens of Wilmington, North Carolina, on the same topic. - Hunt, Alfred N.. Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America : Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean vol 1. Baton Rouge, US: LSU Press, 2006, p. 112

- ↑ "Similarly, in North Carolina militia arms were 'in a tolerable state of use,' the governor was told, though they were aging, having been acquired in 1790 'to be used only in case of insurrection among the blacks, in which event they were to be distributed among the militia.' Then there was the other age-old problem: '[I]f an Indian war should take place,' Governor William Hawkins was informed, as conflict with London crept ever closer, 'and the probability is that it will ultimately be the case, the frontier counties of this state will undoubtedly be very much exposed.' By late 1813, the Royal Navy was lurking off the state’s eastern shore and, it was reported, 'agitation and alarm spread through every part' of the region. While British forces were actually planning to strike Baltimore, due north, the leader of the 'Committee of Safety' in Wilmington, North Carolina, was bothering the governor with the notion that 'their course may be directed to this part of the coast.' - Horne, Gerald. Negro Comrades of the Crown : African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation vol 1. New York, US: NYU Press, 2014, p. 62

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Cecelski, David S.. The Waterman's Song : Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina vol 1. Chapel Hill, US: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. pp. xi, xii, xvi, 128-9, 134, 201

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Anne Russell (2004) [1981]. Wilmington: A Pictorial History. Donning. pp. ix, 1, 7, 9, 15, 24–9, 32, 95, 97, 124. ISBN 9781578642526.

- ↑ New Hanover County Marriages 1855 - 1868, Contributed by Natasha Miles, NCGenWeb.US, November 2009

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Sheila Smith McKoy (13 November 2001). When Whites Riot: Writing Race and Violence in American and South African Cultures. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 42, 44, 137–8. ISBN 978-0-299-17394-4.

- ↑ John Yeamans, wikipedia, June, 2017

- ↑ William Tryon, wikipedia, June, 2017

- ↑ List of Governors of North Carolina, wikipedia, June, 2017

- ↑ Charles Manly, Wikipedia, June, 2017

- ↑ Alexander Manly, wikipedia, June, 2017

- ↑ About Thomas H. Jones, From C. Peter Ripley et al., eds., The Black Abolitionist Papers, vol. 2, Canada, 1830-1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 134-5. Used by permission of the publisher.

- ↑ The Experience of Thomas H. Jones, Who Was a Slave for Forty-Three Years, Electronic Edition. Text scanned, corrected and encoded by Natalia Smith. First edition, 1995, Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1995

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 Sisters watch decades change face of neighborhood, by Ingrid D. Jaffe, Star-News - Jun 28, 1981, p. 15

- ↑ Union North Carolina Volunteers, 1st Regiment, North Carolina Infantry, National Park ServiceU.S. Department of the Interior

- ↑ Civil War 150: U.S. Colored Troops in North Carolina, Aug 20th, 2012 by Genealogical Services.

- ↑ Black Troops at Fort Fisher, North Carolina Historic Sites, Oct 6, 2015

- ↑ Results for Battle Units in Confederacy, North Carolina, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

- ↑ * 10th Battalion, North Carolina Heavy Artillery, Confederate North Carolina Tropps, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

- 17th Regiment, North Carolina Infantry (1st Organization), Confederate North Carolina Troops, National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior

- 18th Regiment, North Carolina Infantry, Confederate North Carolina Troops, National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior

- 1st Battalion, North Carolina Heavy Artillery, Confederate North Carolina Troops, National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior

- ↑ Robert H. Stockman (1985). The Baha'i Faith in America: Origins, 1892-1900. Bahá'í Publ. Trust. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-87743-199-2.

- ↑ Whitehead, O.Z. (1983). Some Bahá'ís to Remember. Oaklands, Welwyn, UK: George Ronald Publisher Ltd. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-85398-148-0.

- ↑ Kurtz, Peter. Bluejackets in the Blubber Room : A Biography of the William Badger, 1828-1865. Alabama, US: University of Alabama Press, 2013, p. 160

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Wilmington, North Carolina's African American Heritage Trail, by Margaret M. Mulrooney, Published 1997, p. 6

- ↑ Public Laws of the State of North-Carolina, Passed by the General Assembly, at Its Session of ... Holden & Wilson. 1869. p. 249.

- ↑ Anne Russell Allibris.com

- ↑ Results for author:"Reaves, Bill, 1934-", HathiTrust.org, June, 2017

- ↑ Search results for 'au:Reaves, Bill,', WorldCat, June, 2017

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 Descendants of David Elias Sadgwar - Generation No. 2, by Charles M. Uzzell, geneology.com

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 General Catalogue of students; 1865-6, Annual catalogue of Lincoln University, by Lincoln University, 1878, p. 29

- ↑ Joseph Kelly Turner; John Luther Bridgers (1920). History of Edgecombe County, North Carolina. Edwards & Broughton printing Company. p. 274.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 ‘Citizen of the year’; Woman strives for harmony, by Kim McGuire, Star-News - Feb 26, 1982, p. 19–20

- ↑ Democratic arguments, The Wilmington Post (Wilmington, North Carolina)03 Sep 1868, Thu • Page 2

- ↑ North Carolina; Teachers and Missionaries, AMA Annual Report, 1869, p. 22

- ↑ The Day of Jubilee!, The Wilmington Post (Wilmington, North Carolina)05 May 1870, Thu • Page 1

- ↑ Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Wikipedia, May, 2017

- ↑ Mechanics' Association, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)7 Oct 1870, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Private Laws of the State of North-Carolina, Passed by the General Assembly at Its Session of ... Holden & Wilson. 1871. p. 59.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 The story of the Jubilee Singers: with their songs by Marsh, J. B. T., Loudin, Frederick J., 1898, pp. 110-111

- ↑ Catherine W. Bishir (2010). "Urban Slavery at Work: The Bellamy Mansion Compound, Wilmington, North Carolina". Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. University of Minnesota Press. 17 (2): 13–32. JSTOR 20839347.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Chris E. Fonvielle, Jr. (January 2007). Historic Wilmington & Lower Cape Fear. HPN Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-893619-68-5.

- ↑ Graduates of the Collegiate Department, Annual catalogue of Lincoln University, 1897, p. 57

- ↑ Howard University (1965). Directory of Graduates: Howard University, 1870-1963. Howard University. p. 323.

- ↑ Schools, The Evening Post (Wilmington, North Carolina)20 Jun 1872, Thu • Page 2

- ↑ County commissioners, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)4 Oct 1872, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Graded and Highs-schools; Williston School Wilmington NC, AMA Annual Report, 1870, pp. 27-8

- ↑ Williston High School’s origins date to Civil War, By Ben Steelman, StarNews Online, May 26, 2015

- ↑ The roof of a house…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)16 Feb 1873, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ Board of aldermen, The Daily Journal (Wilmington, North Carolina)16 Jan 1875, Sat • Page 4

- ↑ Industrial fair exposition, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)28 Dec 1875, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ The colored Normal School, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)1 Apr 1877, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ Sheriff's Wilmington, N.C. directory and general advertiser for 1877-8; "S", by Sheriff R. Benjamin, p. 137

- ↑ Delegates to the state convention, The Wilmington Post (Wilmington, North Carolina)20 Jun 1880, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ * Independent Order of Immaculates, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)24 Jul 1880, Sat • Page 1

- Notice - I O I, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)8 Jan 1882, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ For more on the hospital see brief mention at Historical Notes - General Hospital No.4, by R. J. Cooke, Old New Hanover Genelogical Society, 2005 and North Carolina’s First Hospital, by Dr. Martin Rozear, Ocracoke Newsletter, August 21, 2011

- ↑ the US Marine Hospital in Wilmington and matters of interest connected with it, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)14 Aug 1881, Sun • Page 4

- ↑ To the total amount paid…, The Wilmington Post (Wilmington, North Carolina)15 May 1881, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ The Budget: Containing the Annual Reports of the General Officers of the African M. E. Church of the United States of America; with Facts and Figures, Historical Data of the Colored Methodist Church in Particular, and Universal Methodism in General; Together with Religious, Educational and Political Information Pertaining to the Colored Race. Tourchlight Printing Company. 1881. p. 139.

- ↑ Railroad matters, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)18 Jan 1883, Thu • Page 1

- ↑ Railroad matters, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)19 Jan 1883, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ List of jurors, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)5 Mar 1883, Mon • Page 1

- ↑ * The following have been…, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)21 Apr 1883, Sat • Page 1

- The following mail carriers…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)22 Apr 1883, Sun • Page 1

- The free delivery, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)30 Apr 1883, Mon • Page 1

- ↑ Johnson C. Smith University, Wikipedia, May, 2017

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 The available archive is missing the following year which would have been his last year. - Annual catalog, by Biddle University(Johnson C. Smith University), 1934, pp. 29, 56

- ↑ Mrs. Sadgwar is visiting…, The Banner-Enterprise (Raleigh, North Carolina)19 Jul 1883, Thu • Page 3

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 A Report to Abdul Baha of the Bahai Activities in the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, by Charles Mason Remey, 1919-06-07

- ↑ Republican primaries, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)24 Apr 1884, Thu • Page 1

- ↑ A full house greeted…, The Banner-Enterprise (Raleigh, North Carolina)9 Aug 1884, Sat • Page 3

- ↑ Died, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)08 Jul 1887, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Republican primaries, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)18 Mar 1887, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Receipts and Expenditures of the Senate; Stateement of disbursements from the contingent fund, & etc, United States congressional serial set, by the US, GPO, p. 42, 46

- ↑ Statement of Disbursements from the Contingent Fund, etc…; Furniture and repairs fiscal year 1887, Receipts and expenditures of the Senate, published by the U.S. G.P.O., 1889, p. 52, 55

- ↑ Russel’s “savages", The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)19 Aug 1888, Sun • Page 1

- ↑ The “Independent Republicans"…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)21 Aug 1888, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ Russell's 'Savages', The Weekly Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)24 Aug 1888, Fri • Page’1

- ↑ Patents Publication number US405117, Publication date Jun 11, 1889, Filing date Aug 27, 1888, District of US 405117 A

- ↑ Officers and employés of the Senate, Official register of the United States containing a list of the officies and employes …], vol 1, GPO, July, 1889, p. 8.

- ↑ Entertainment to-night, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)20 Mar 1889, Wed • Page 4

- ↑ Miss Pauline A. Knobloch…, Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia)09 Nov 1893, Thu • Page 5

- ↑ A large funeral concourse, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)9 Jan 1889, Wed • Page 1

- ↑ Sale of land for taxes!, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)13 Jan 1889, Sun • Page 3

- ↑ Board of aldermen, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)5 Mar 1889, Tue • Page 5

- ↑ The last city election, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)12 Mar 1889, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ * County commissioners, The Daily Review (Wilmington, North Carolina)6 May 1890, Tue • Page 1 • Criminal court, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)20 May 1890, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ Gregory Institute, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)28 May 1890, Wed • Page 8

- ↑ * The Board then went…, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)3 Mar 1891, Tue • Page 8

- Certificate of election, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)28 Mar 1891, Sat • Page 1

- ↑ * University societies, The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee)06 Jun 1891, Sat • Page 5

- ↑ 94.00 94.01 94.02 94.03 94.04 94.05 94.06 94.07 94.08 94.09 Gayle Morrison (1 January 1982). To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Unity in America. Bahá'í Pub. Trust. pp. 3–6, 16, 18, 35, 123–5, 151, 155, 164, 185–91. ISBN 978-0-87743-171-8.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Anne Russell; Marjorie Megivern; Kevin Coughlin (April 1986). North Carolina portraits of faith: a pictorial history of religions. Donning Co. p. 232.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 "Campus news and notes". The Fisk University News. Vol. 7, no. 3. Fisk University. February 1917. p. 32.

- ↑ Fisk University bulletin; Students, pp. 17, 19, 15.

- ↑ * Exercises at Fisk, The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee)12 Jun 1894, Tue • Page 4

- At Fisk University, The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee)14 Jun 1894, Thu • Page 3

- ↑ Mass meeting of colored citizens, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)4 Sep 1891, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Wilmington Notes; Mr. and Mrs. F. C. Sadgwar…, Africo-American Presbyterian, (Wilmington, NC), August 20, 1891, p. 3, 1st col, above-mid

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 [1], Annual Reports of the American Missionary Association, 1892-1910, pp. 47, 61,

- ↑ Inborden, Thomas Sewell, by Ralph Hardee Rives, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 volumes, edited by William S. Powell, 1988

- ↑ * The committee then reported…, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)30 Oct 1891, Fri • Page 4

- Republican primaries, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)1 Apr 1892, Fri • Page 1

- The republicans, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)28 Aug 1892, Sun • Page 1

- What does it mean?, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)14 Oct 1892, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ The Republicans had…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)19 Oct 1892, Wed • Page 1

- ↑ Board of Canvassers, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)11 Nov 1892, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Board of Aldermen, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)8 Mar 1893, Wed • Page 1

- ↑ Certificate of election, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)24 Mar 1893, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Jurors were drawn…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)6 Jun 1893, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Johnson C. Smith University (1904). Annual Catalogue. Johnson C. Smith University. p. 81.

- ↑ The Colored K. of P., The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)31 Aug 1894, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Knights of Pythias, Wikipedia, May, 2017

- ↑ * Business more essential than politics, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)2 Sep 1894, Sun • Page 1

- The colored business men organize a business league, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)2 Sep 1894, Sun • Page 8

- ↑ The Colored K. of P., The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)21 Sep 1894, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Emancipation celebration, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)02 Jan 1895, Wed • Page 4

- ↑ For charitable work among colored people, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)6 Jan 1895, Sun • Page 8

- ↑ The fund entertainment, The Southport Leader (Southport, North Carolina)27 Jun 1895, Thu • Page 4

- ↑ A stormy meeting, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)25 Oct 1895, Fri • Page 1

- ↑ Bolt in the first ward, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)27 Mar 1896, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Washington letter, The Messenger and Intelligencer (Wadesboro, North Carolina)4 Jun 1896, Thu • Page 2

- ↑ Damon and Pythias, The Washington Bee (Washington, District of Columbia)1 Aug 1896, Sat • Page 8

- ↑ Editor Gazette, The Gazette (Raleigh, North Carolina)13 Feb 1897, Sat • Page 2

- ↑ Knights of Pythias meet, Richmond Planet (Richmond, Virginia)24 Jul 1897, Sat • First Edition • Page 3

- ↑ Knights of Pythias meet, Richmond Planet, (Richmond, Virginia,) 24 July 1897, p. 3 (1st col bottom left)

- ↑ New corporation, News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina)15 Aug 1897, Sun • Page 8

- ↑ A sudden death, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)22 Jan 1898, Sat • Page 1

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 State of North Carolina, County of New Hanover…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)2 Sep 1904, Fri • Page 2

- ↑ Tax lein…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)01 Feb 1901, Fri • Page 3

- ↑ The wife of Geo. W. Price, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)22 Feb 1898, Tue • Page 1

- ↑ Died, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)05 Mar 1898, Sat • Page 4

- ↑ A white man cuts a colored man, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)6 Mar 1898, Sun • Page 6

- ↑ His bike should have possessed a belt, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)10 Jun 1898, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Manly, Alex (1866-1944), by Lucy Burnett, U. of Washington, BlackPast.org v2.0, 2017

- ↑ * The Committee at work, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)10 Nov 1898, Thu • Page 1

- Further action, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)10 Nov 1898, Thu • Page 5

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 David S. Cecelski; Timothy B. Tyson (9 November 2000). Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy. University of North Carolina Press. p. 17, 20, 63. ISBN 978-0-8078-6657-3.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 Tape Log -- Lewin Manly, Interview number C-0352 from the Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) at The Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, @ 5:03

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Fisk University (1901). Catalog of the Officers, Students and Alumni of Fisk University. The University. pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Your results for: wilmington race riot, Nov 11, 1898, Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited

- ↑ Your results for: sadgwar, Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited

- ↑ Your results for: "jubilee singers" fisk, November, 1898, Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited

- ↑ Typescript of letter written by Alex Manly's widow Caroline "Carrie" Sadgwar Manly, Date: Jan. 14 1954, ECU Libraries, East Carolina University, p.2

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963 for Byron Sadgwar (registration required) Ancestry.com

- ↑ U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 for Byron Sadgwar, New Jersey Atlantic City 1 Draft Card S, (registration required) Ancestry.com

- ↑ New York, Spanish-American War Military and Naval Service Records, 1898-1902 for Byron Sadgwar, (registration required) Ancestry.com

- ↑ Remembering 1898:Literary Responses and Public Memory of the Wilmington Race Riot by J. Vincent Lowery, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report Final Report, May 31, 2006, North Carolina Office of Archives & History

- ↑ Biographical Sketches of Key Figures, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report Final Report, May 31, 2006, North Carolina Office of Archives & History, pp. 270-1, 273-4, 276-7

- ↑ Chapter 2: Forces of Change, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report Final Report, May 31, 2006, North Carolina Office of Archives & History, pp. 48–51

- ↑ Chapter 4: Eve of Destruction, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report Final Report, May 31, 2006, North Carolina Office of Archives & History,p. 119

- ↑ Appendix K; City Directory Data,1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report Final Report, May 31, 2006, North Carolina Office of Archives & History, p. 388

- ↑ Bids for repairing…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)8 Nov 1899, Wed • Page 1

- ↑ George Henry White, Wikipedia, May, 2017

- ↑ Licenses to Wed, The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland)05 Jun 1901, Wed • Page 2

- ↑ Marriage licenses…, The Appeal (Saint Paul, Minnesota)08 Jun 1901, Sat • Page 2

- ↑ Marriage Licenses, Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia)04 Jun 1901, Tue • Page 3

- ↑ Cards are out…, The Colored American (Washington, District of Columbia)01 Jun 1901, Sat • Page 12

- ↑ Fisk University (1901). Catalog of the Officers, Students and Alumni of Fisk University. The University. p. 88.

- ↑ National Decoration Day, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)30 May 1901, Thu • Page 4

- ↑ Law class to graduate, The Washington Times (Washington, District of Columbia)22 May 1902, Thu • Page 8

- ↑ Splinter in his eye, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)14 Sep 1901, Sat • Page 4

- ↑ American Missionary Association (October 1901). Report. p. 61.

- ↑ United States. Civil Service Commission (1911). Official Register of the United States: Persons Occupying Administrative and Supervisory Positions in the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Branches of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia Government. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 692.

- ↑ Gregory Normal Institute, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)23 May 1902, Fri • Page 4

- ↑ Miss Letitia Cottman…, The Colored American (Washington, District of Columbia)27 Sep 1902, Sat • First Edition • Page 2

- ↑ North Carolina (1905). Public Documents. p. 45.

- ↑ Robert H. Stockman (1985). The Bahá'í Faith in America: Early expansion, 1900-1912. Bahá'í Pub. Trust. pp. 80, 135–137, 224–6, 343–6. ISBN 978-0-85398-388-0.

- ↑ School building burned, The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina)10 Feb 1904, Wed • Page 4

- ↑ "Receipts". The American Missionary. Vol. 58, no. 4. American Missionary Association. April 1904. p. 158.

- ↑ Commissioner's sale, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)10 Mar 1905, Fri • Page 2

- ↑ Build colored Manse, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)3 Jun 1905, Sat • Page 1

- ↑ Marriages, New Jersey Marriage Index (Brides) - 1904-1909 - Surnames T-Z, 1904, p. ?

- ↑ Do We Have Spiritual Ancestors? Meet Pocahontas Pope, by Christopher Buck, Bahaiteachings.org Sep 15, 2016

- ↑ Pocahontas Pope, Bahaichronicles.org

- ↑ Real estate transfers, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)20 Mar 1907, Wed • Page 1

- ↑ Louis George Gregory, Wikipedia, 2017

- ↑ American Missionary Association (1910). Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. The Association. p. 4.

- ↑ Fisk University (1900). Catalog of the Officers, Students and Alumni of Fisk University. The University. p. 183.

- ↑ Progress of training school, The New York Age (New York, New York)5 Jan 1911, Thu • Page 8

- ↑ Gregory Normal Institute, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)14 Feb 1912, Wed • Page 2

- ↑ * Gregory Normal Institute, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)16 May 1912, Thu • Page 6

- Closing at Gregory Normal, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)23 May 1912, Thu • Page 5

- ↑ List of teachers, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)02 Oct 1912, Wed • Page 8

- ↑ Entries announced; Colored people, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)17 Apr 1913, Thu • Page 4

- ↑ * Names announced, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)18 Jun 1913, Wed • Page 7

- Williston colored school, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)6 Oct 1913, Mon • Page 5

- Williston colored school, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)12 Jun 1914, Fri • Page 5

- Williston Industrial (Colored), The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)1 Jun 1915, Tue • Page 5

- Williston Industrial, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)18 Sep 1915, Sat • Page 5

- ↑ American Missionary Association (October 1913). Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. American Missionary Association. p. 45.

- ↑ American Missionary Association (October 1914). Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. American Missionary Association. p. 44.

- ↑ American Missionary Association (October 1915). Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. American Missionary Association. p. 40.

- ↑ American Missionary Association (October 1916). Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. American Missionary Association. p. 40.

- ↑ Three houses entered by burglars Sunday night, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)25 Apr 1916, Tue • Page 5

- ↑ Summer School attendants 1916, Bulletin of A. & T. College, (Greensboro, N.C.) 1917, p. 96

- ↑ * Colored schools, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)22 Jul 1916, Sat • Page 6

- Colored pupils get high marks, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)4 Mar 1917, Sun • Page 6

- Williston Industrial School, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)30 Sep 1917, Sun • Page 7

- ↑ State of North Carolina, County…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)1 Nov 1916, Wed • Page 3

- ↑ Sadgwar, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)27 Feb 1917, Tue • Page 6

- ↑ * Premiums ready for fair winners, The Wilmington Dispatch (Wilmington, North Carolina)2 Dec 1917, Sun • Page 7

- Winners at colored fair, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)2 Dec 1917, Sun • Page 9

- ↑ * Lawyers at Court House, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)16 Dec 1917, Sun • Pages 5–6

- State occupation clearly, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)19 Dec 1917, Wed • Page 5

- Afternoon, at Jervay's…, The Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, North Carolina)21 Dec 1917, Fri • Page 5

- ↑ Talks universal peace, The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware)19 Mar 1917, Mon • Page 3

- ↑ Program for Green Acre Conferences, The Portsmouth Herald (Portsmouth, New Hampshire)06 Aug 1917, Mon • Page 4